Dear Baby Boomers,

Aaron Sorkin calls us, the Millennials, the Worst (pause) Generation (pause) ever.

And he must be right. Just look at those tattooed necks and gauged ears. We are characterized by an unwillingness to work, unwillingness to leave home, a need for redirection, praise and general over-entitlement. So, we Jersey Shore-watching, mewling, Lindsay Lohan-worshipping, selfie-snapping, YOLO morons must be the worst, right?

Certainly that's a fair label to place on us. The oldest among us right now would is already 32 after all (though most of us are in our 20s). You guys all had things totally figured out during your 20s, right?

More to the point, Boomers, what exactly have you done that was so great? Landed us on the moon? Your parents did that. Created life changing inventions and innovations? The most important invention to come along during your time (the internet) - again - had its genesis with your parents. Have you made life aggregately better for people in society? Not really. Not by most metrics.

In fact, since these statistics have been tracked, my generation is the first one in history not likely to substantially eclipse our parents in terms of quality of life or inflation-adjusted income.

During your parents generation, life expectancy increased by 30% or 18 years. During your generation? 10% or 7 years.

You spent your entire younger years protesting the unjust wars to which your parents sent you and then what did you do when you took the reins? Sent us on several more, killing my generation by the thousands in an act of mind-boggling hypocrisy. And just for laughs - if it's possible - the Iraq War was even more misguided and unnecessary than Vietnam.

After we finally routed out McCarthy and Red Scare hysteria? You all come swooping in with anti-Islamic hate-mongering.

You complained about how your parents didn't understand you and judged

your music while doing exactly the same thing to hip hop. This, even

after GenX and the Millennials embraced their parents music like no

generations before. The Beatles and Stones still do astounding levels of business. Find me a 25 year old who thinks Beyonce is queen bee and I'll find you another who thinks music peaked in 1972. The culture wars are over. You won through sheer attrition.

Your parents presided over the greatest period of American prosperity in the history of the country (and, in many ways, the most equitable). You? You created a sputtering prosperity based on an endless series of economic bubbles that vastly rewards the wealthy over everyone else.

Your parents created a safety net FOR YOU and you've spent your entire time trying to cut it for both them and us while your generational prosperity comparatively grows. Those of prime working age have never had better while the glut of foreclosures and evictions as well as systematic labor demographics disproportionately and negatively affect the young and the elderly.

Your parents and grandparents and everyone before them saved money and then you stopped. The mantra of this country was to leave the world better for their children then when they found and yours was the first concerned primarily with itself.

Your parents gave us The New Deal, The Great Society, Brown v Board of Education, The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Clean Air and Clean Water Acts. What did you give us? The War on Drugs? Welfare reform? The Defense of Marriage Act? The repeal of Glass-Stegall? Tax cuts (for yourselves)? Tax cuts (for the rich)? AN ENDLESS MOTHERFUCKING DRUMBEAT ABOUT THE DANGERS OF OBAMACARE? Socialized medicine will be the end of us. Enjoy your Medicare.

During your parents generation, we got Truman, Eisenhower, Johnson and Kennedy - each with failings, certainly, but each with a series of equanimity-based policy accomplishments staggering by today's standards. And once you all "tuned in and turned on," we got Nixon, Reagan, Clinton and 2 Bushes - the worst string of Presidents since the end of the 19th century. Almost worse than that, by your sheer numbers, insistence and half-cocked dumbass reasoning that Reagan single-handedly ended the coldwar on June 12, 1987 now we have to deal with him in the Pantheon of great presidents. Bad news, friends. He's not.

You've created a society in which housing costs a higher percentage of income than at any point since the Depression. You've made it so that we're tens of thousands of dollars in debt - not as a perk - but as a requirement before we even enter the workforce. You gave us the highest divorce rate ever. You failed to update GI Bill to equitable levels while you have us fighting in the longest wars in our country's history. You put up every barrier you possibly could to our collective generational success and before we've even gotten the reins, you call us the worst generation ever.

What the fuck did you ever do? Seriously, what do you imagine your legacy to be? What exactly is it that you're all so proud of?

We embraced your music and culture. We more or less listened to your advice and became more cautious. We are the most post-material, team-playing, empathetic generation in history by any demographic study. We became exactly what you wanted and now you turn on us before we even have our first time up at bat.

If you feel anything I wrote was unfair or didn't apply to you, imagine how we feel. You've had 40 years of dominance. We haven't even had our time yet. And it's not like your time was any great shakes.

Friday, June 22, 2012

Sunday, February 5, 2012

SPORTS: What is greatness? Meditations on the 2011 New York Giants

In recent years, my beloved Giants have developed a bit of a narrative pattern each season: a strong start followed by a near-complete meltdown halfway before an occasional on-the-fly re-invention as unflappable fourth quarter warriors. It's an odd feeling to watch a team you love but never once believed was the league's best back into two Super Bowls in four years. Odd but wonderful. With hindsight, it's hard not to ask: what is this team? I don’t mean these past few weeks or even this season. Going back a few years – what is this team? What should we make of them?

This is a team without a specific personality or organizing principle. Of late, the Giants are usually elite as a pass rushing unit combined with what is almost always one of the worst secondaries in the league, 6 or so years running. They are a team that occasionally gets superb years out of cast-offs like Ahmad Bradshaw but still can’t convince Brandon Jacobs to run like he weighs 260 lbs. This is a team that literally can’t find enough space for all their phenomenal defensive line talent (notably lining up Jason Pierre-Paul at tackle to make room) but hasn’t drafted an all-pro line-backer since Jessie Armstead in 1993. This is a team that, in 2003, drafted what turned out to be the best quarterback available that year but packaged him with other picks (one of which became Shawne Merriman) in order to get a lesser quarterback with more name recognition.

And, yet, it’s all almost genius in its own way, isn’t it?

We’ve now won 2 Super Bowls in 4 years which is a very, very impressive feat given that this team really isn’t very good. Or are they? Seriously, what is this team?

This is the New York Giants in the era of Tom Coughlin and Eli Manning.

Tom Coughlin

Three years after taking his team to the Super Bowl, Coach Jim Fassel was unceremoniously fired following the Giants 39-38 meltdown against the 49ers in the 2002 playoffs and the injury-racked 2003 season. The line on Fassel was always that he was too friendly with his players. He led a sloppy show, cow-towed to his veterans and countenanced a team that, above all, lacked discipline.

I like that word discipline a lot in sports narratives – it covers all manner of sins in without really meaning anything. As if these players – these unbelievably fast, strong machines with bodies carved out of stone – would devolve into a fourth grade gym class without a stern, John Wayne, hardass keeping them in line.

I like that word discipline a lot in sports narratives – it covers all manner of sins in without really meaning anything. As if these players – these unbelievably fast, strong machines with bodies carved out of stone – would devolve into a fourth grade gym class without a stern, John Wayne, hardass keeping them in line.

Enter Tom Coughlin, a man who’s primary claims to the moment of his hire had been his leading the Jacksonville Jaguars to an entirely improbable run at the AFC Championship and for the perception around the league that he didn’t take any guff from his players.

Instantly, Coughlin alienated veterans Michael Strahan and Tiki Barber with his dogmatism and capricious disiplinary regime, instituting a schedule of mandatory fines for being late to meetings and two-a-day practices in the summer heat designed to, I don’t know, kill the players, probably.

The old grumpy old white guy sports media could not praise him often or vociferously enough. Discipline was the watchword of the new Coughlin administration.

Instantly, Coughlin alienated veterans Michael Strahan and Tiki Barber with his dogmatism and capricious disiplinary regime, instituting a schedule of mandatory fines for being late to meetings and two-a-day practices in the summer heat designed to, I don’t know, kill the players, probably.

The old grumpy old white guy sports media could not praise him often or vociferously enough. Discipline was the watchword of the new Coughlin administration.

The funny thing about discipline in football is that unlike most other sports "intangibles" hot-taking call-in radio prefer, there are constructs that allow for measurement. Simply put, a disciplined team should not get hit with penalties. While it’s not fair to look at one year and say whichever team got the least number of penalty yards was the most disciplined, over a period of years it gives a fair assessment of a team's disciplinary culture. Over the last seven years the Giants have ranked 13th, 16th, 19th, 27th, 11th, 26th and 27th out of 32 teams leaguewide in penalty yards where higher is better. Read those numbers again and I imagine you were being paid millions of dollars based on the specific and affirmative notion that you engendered a disciplined environment. Coughlin's Giants have never once been among the most disciplined teams in the league and several times, they've been among the least.

Besides demonstrably failing at the one thing for which he was hired, Coughlin is among the least creative play-callers and formation designers in football. He calls a solid, unspectacular game that rarely embraces the particular strengths of the team as it evolves. Coughlin's offensive gameplan has not substantively changed at all during his eight-year tenure. For example, his go-to short yardage goal line play has been an over-the-top corner fade. In 2005, when the Giants has Plaxico Burress, a 6'5" superathlete, as their primary weapon, it was a fine and effective strategy. Today, it makes a lot less sense. Now, I’m not saying I want Coughlin to jump on every idiotic bandwagon that rolls through the NFL (I’m looking at you Wildcat formation) but Coughlin has demonstrated that he is an old-school guy locked fast in an outmoded way of thinking, especially offensively.

Coughlin's inability to learn and adjust is beautifully illustrated by Brandon Jacobs. I was shocked – fucking shocked – to learn that Brandon Jacobs holds the team record for rushing touchdowns with 52. This might imply that Jacobs is a great running back, especially in short yardage situations. What it really means is that Jacobs has been given chance after chance after chance after chance while Coughlin learns nothing about his true abilities and makes no adjustments. Of these 52 touchdowns, 27 of them, or a little over 50% have come from rushes within 2 yards. This is despite the fact that Jacobs fails in short yardage situations 20% more often than the average running back. Any average NFL running back would have more luck scoring in short yardage situations and yet, Coughlin has been beating his head against that same brick wall – not for 1 year, not 2… 7 years. Why? Why does a below average short yardage running back now hold the Giants franchise record for short yardage touchdowns? Because Jacobs looks like a great short yardage back, and therefore Coughlin simply can not accept the reality that he isn't actually great in that situation. In 7 years Coughlin has stubbornly refused to implement anything new for this team. For what its worth, of Ahmad Bradshaw’s 18 touchdowns, only 17% have come from within 2 yards. Coughlin has probably cost himself at least a couple of wins by this personnel misuse alone. It's really inexcusably stubborn.

Coughlin will, from now on, receive favorable comparisons to a lot of great coaches… Parcells, Belichick, etc. But I found a piece in particular that had a comparison I really like: Coughlin is Tim Tebow. While that author meant it as a compliment (“When the critics put his back against the wall and put his job in jeopardy all he does in win”), I don't. I mean it in the least complimentary way possible. In the same way that Tebow is showered with credit that righly belongs to others (namely, his defense) and in the same way that Tebow manages to fall ass-backwards into dramatic, memorable wins, then yes, Coughlin is the Tebow of coaches.

The problem with this Super Bowl (and winning the Super Bowl is a very good problem) is what it means for the Giants long-term. Somehow, Tom Coughlin is now a multi-Super Bowl winning coach, which means it’s going to be some time before we’re able to get rid of him. I know it sounds crazy to be counting the hours until your multi-Super Bowl winning coach is out the door but we're playing with house money right now, and my preference would be to move to the cashier - not another craps table. More Coughlin means the Giants yearly ritual of starting strong before a second half that runs the gamut from mediocrity to complete collapse will continue indefinitely. Indeed, the Giants have never - not once - done as well or better in the second half of the season as they did during the first under Tom Coughlin. They are 47-17 through the first 8 games under Coughlin and 28-36 in the second 8.

The problem with this Super Bowl (and winning the Super Bowl is a very good problem) is what it means for the Giants long-term. Somehow, Tom Coughlin is now a multi-Super Bowl winning coach, which means it’s going to be some time before we’re able to get rid of him. I know it sounds crazy to be counting the hours until your multi-Super Bowl winning coach is out the door but we're playing with house money right now, and my preference would be to move to the cashier - not another craps table. More Coughlin means the Giants yearly ritual of starting strong before a second half that runs the gamut from mediocrity to complete collapse will continue indefinitely. Indeed, the Giants have never - not once - done as well or better in the second half of the season as they did during the first under Tom Coughlin. They are 47-17 through the first 8 games under Coughlin and 28-36 in the second 8.

Offensive Coordinator Kevin Gilbride and Tom Coughlin are by no means the worst offensive minds in football, but they might be the worst to have ever received their particular brand of extended tenure.

Eli Manning

Eli Manning, for his part, constantly makes me question the nature of what it is to be great. Eli is not a great quarterback. In 2010, I had him ranked 12th best in the league, this year I would say he cracked the top 10, but not the top 5. In the land of NFL quarterbacks he hovers somewhere around mediocre. Often, though, I would call Eli simply “good.” He will occasionally ratchet that up to “very good” and that above all else is what’s so maddening about him as a player. That above all, is why I don't know how I feel about him as my team’s quarterback, both historically and moving forward.

I never understood what it was that people liked so much about a player being “clutch.” First of all, as a person who tries not to blindly ignore observable patterns, I’m a scion of the idea that while clutch performances exist, clutch players do not. Regardless assume a clutch skill exists for a moment. I've spent a shameful amount of my life listening to sports talk radio guys applaud players for having that “extra gear” they can shift into “when it counts.” I’m left wondering why anyone would want that. If a guy has an “extra gear” shouldn’t we be pissed he isn’t using it all the time? Doesn’t that imply “clutch” players aren’t always trying their hardest?

Eli isn’t exactly considered “clutch” but much has been made of how much better he plays in the 4th quarter, especially this season. While others congratulate him for that, it drives me nuts. Eli clearly has all of the tools, physically, and in his surrounding personnel to be an elite quarterback but he’s consistently held back by bad decision-making. He throws way too many stupid passes and a lot of them are picked off. Watching him these last few weeks, though, really drives home – he fucking could be the best quarterback in the league, but he just isn't. Why? I honestly have no clue. Maybe he’s just not driven by that phantom desire for greatness. Maybe he realizes it's a crapshoot. Maybe he figures God has ordained that he luck into a shot at the Super Bowl every 4 years and his penance is that in the years when the team really is great – like in 2008 – they don’t make it past the first round.

And now we're going to have to endure the interminable questions of whether Eli is better than his brother Peyton. Peyton Manning, for my money was, up until probably 3 years ago the unquestioned greatest quarterback of all time. With the good statistical years Brady had in the championship days giving way to some absolutely stupid amazing performances since 2007, I think the gap has closed such that either one has a fair argument for the crown.

The Eli vs. Peyton debate is different, though, and more insidious. It says something about us and what we believe “greatness” is. Peyton Manning is not only a great athlete, but a brilliant football tactician who basically served as his teams de facto offensive coordinator for nearly his entire career. Without him, a 10-6 Indianapolis team only 2 years removed from a Super Bowl win with roughly the same roster collapsed, becoming the unquestioned worst team in the NFL in 2010. Peyton’s credentials should be absolutely beyond reproach. Yet the question will be asked over and over again: "is Eli better than his brother because he has more championships?"

The answer should be, of course, "No. No. No, he's not. Eli's not even close to better than Peyton. He's not in the ballpark of being better. He's not in the parking lot of that ballpark. He's not in driving distance of the parking lot of the ballpark where he might be better than Peyton" But, for many, the answer will likely be a simple, unequivocal "yes," and this kicks off the insidious referendum on greatness I referred to earlier. Somehow, all the work – all the fantastic, unprecedented work Peyton Manning has done gets erased by a lucky 4 months for the Giants - 2 in 20007-08 and one in 2011-12. This is the same impulse that lets us look at a Donald Trump on the one hand and a hard-working, unemployed family man on the other and declare one a success and one a failure without in any context, whatever.

We don’t care about the journey, we don't have time for process. We want results. Doesn't matter if you did the right thing or not. Doesn't matter if you worked hard or not. Doesn't matter if you were lucky or not. Count up the Super Bowl rings, tabulate a guy’s bank account and we've learned all we need to know. "Luck" is the convenient excuse of a loser.

Why do we bother keeping track of these athletes statistics to the third decimal place if we intend to ignore them? Joe Montana is better than Dan Marino. Why? Well, Joe Montana has 4 Super Bowl rings. Well, Joe Montana also had Ronnie Lott and Jerry Rice. Joe Montana had a better tactician for a coach. You know, the guy who invented the offense they were using. Forget a nuanced examination the facts, let’s get something quick and dirty and move on. We've got winners to declare here, people.

Eli Manning is the living embodiment, for and against, all of our worst and most reactionary impulses about what it means to be a success. I’ve never thought he was good enough to be a Championship quarterback, even after 2007 – a Super Bowl victory I thought belonged to the Giants line and Steve Spagnuolo - and, in my head, only incidentally involved Eli. But tonight, having watched my team hoist their second trophy in four years? I don’t have the slightest clue what to think anymore. By definition, Eli must be a championship caliber quarterback but, if he is, then that designation has been devalued.

Eli Manning could be one of the greats, but now that his legacy in that regard is pretty much locked in, the incentive to be pushing himself much harder to achieve that Aaron Rodgers, Tom Brady level is more or less gone. Eli's place in their company has been, right or wrong, guaranteed by the number of rings he’s won even if that ring belongs a lot more to Jason Pierre-Paul, Hakeem Nicks and Chris Snee than it does to him.

The Super Bowl is meant to be the culmination of a long process of planning and execution. You amass the pieces over a period of years and when the moment is right, with a little bit of luck, you charge at the prize. The Giants, however, are more like this constant rebuilding projects with short, staccato burst of greatness that just happened to be timed perfectly. I don’t believe in the idea of momentum in sports. That having been said, watching the Giants these past few weeks I’m definitely not the steadfast an un-believer I once was.

In the same vein, I don’t ever believe a team “owns” another team -- but damned if it doesn't seem like the Giants own the Patriots in a big spot.

In the same vein, I don’t ever believe a team “owns” another team -- but damned if it doesn't seem like the Giants own the Patriots in a big spot.

Last night’s Bowl victory is probably not the start of a long dynasty. If anything, it's as likely to make the Giants complacent and lazy. But a Super Bowl win is a win and it feels wonderful for now just the same.

The magic of sports is that since it’s not pre-determined, the best team doesn’t always - or even usually - win. Last night, the best team did not win.

I just wonder about the way we experience sports, rationalize it, drench it in hindsight bias and devalue the achievements of people just because of the one moment, the one time. The fact that less-than-great people are capable of great moments should be a sign of hope to all of us who are not - strictly speaking - extraordinary.

But, if we are all defined by a few moments when we were at our best or worst than we risk losing the flavor of the smaller moments in life. And there's a hell of a lot more small moments than big ones. Sports is supposed to be this amplified reality that only tangentially reflects real life but it informs the way we view the world, and this particular win and these particular people embody a translation of ideas from sports that I find deeply troubling.

I know I'm going to have to have the same argument over and over again with other Giants fans explaining how I could possibly not see the obvious greatness of Eli Manning. How could I turn on our boy? Those endless picks and poorly conceived ropes into triple-coverage may be long forgotten memories to them but I remember the failures - the late season swoons and the routine collapses. One game doesn't erase all that. Eli is not any one narrative -- many of them are right and many are wrong in equal measure. One game doesn't change who he is as a person or a professional.

I just wonder about the way we experience sports, rationalize it, drench it in hindsight bias and devalue the achievements of people just because of the one moment, the one time. The fact that less-than-great people are capable of great moments should be a sign of hope to all of us who are not - strictly speaking - extraordinary.

But, if we are all defined by a few moments when we were at our best or worst than we risk losing the flavor of the smaller moments in life. And there's a hell of a lot more small moments than big ones. Sports is supposed to be this amplified reality that only tangentially reflects real life but it informs the way we view the world, and this particular win and these particular people embody a translation of ideas from sports that I find deeply troubling.

I know I'm going to have to have the same argument over and over again with other Giants fans explaining how I could possibly not see the obvious greatness of Eli Manning. How could I turn on our boy? Those endless picks and poorly conceived ropes into triple-coverage may be long forgotten memories to them but I remember the failures - the late season swoons and the routine collapses. One game doesn't erase all that. Eli is not any one narrative -- many of them are right and many are wrong in equal measure. One game doesn't change who he is as a person or a professional.

I thank you, Eli Manning and the Giants, for the championships, the fun and the moments of joy but you still suck.

Tuesday, November 8, 2011

POLITICS: Empowerment and Education: Why Young People Don't Vote

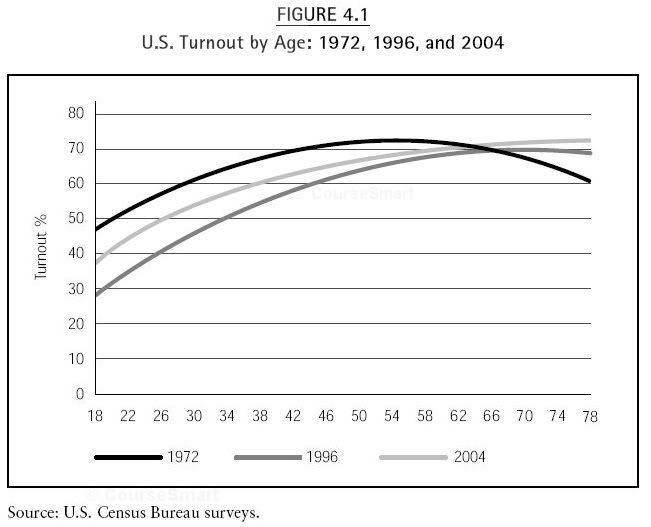

"In the immediate aftermath of the Twenty-sixth Amendment’s passage, nearly eleven million new voters joined the general electorate. More than 50% of eligible voters between the ages of eighteen and twenty-four participated in the 1972 presidential election." (Troy 596). Since then voter participation on the part of young people has dropped precipitously. There are a lot of easier answers floating around to try to explain the maddening phenomena of why young people, whom so many hoped (and continue to hope), would inject energy and vitality into the political system fail so consistently to do so. The answer to why young people do not vote in comparable numbers to the rest of society cannot be neatly summed up but that hasn't stopped scholars and pundits alike from trying. In the end, there is no one answer.

Exploring the type of easy-answer theories they have been posited in the past and subsequently revealed to be on shaky empirical ground (or outright disproven) will be instructional as we will be able to observe what misconceptions they led to and how we can avoid them in the future. One theory that seems logical enough on its face is posited in The American Voter Revisited. Lewis-Beck states that younger voters have lesser roots; that the pedantic fineries of politics may be of little interest to young people since the policies enacted don’t effect them directly:

Another hypothesis, posed by Martin Wattenberg and many others, is that for various reasons - apathy, cynicism, laziness - young people are less politically knowledgeable than they were decades ago. "Today when it comes to political news stories, one could reasonably say, 'Dont ask anyone under 30,' as chances are good that he or she won’t have heard of these stories. Young adults today can hardly challenge the establishment if they don’t have a basic grasp of what is going on in the political world" (Wattenberg 61). This line of reasoning is not only reductive, it suffers from a serious chicken-egg problem. Mr. Wattenberg fails to elucidate whether or not lack of political knowledge led to lower turn-outs or the other way around. What Mr. Wattenberg does state is that for the few that still do vote, their comparative lack of knowledge leads them to be ineffective voters: "[W]e will examine data on whether people of different age groups say they have followed major political events. This is important in and of itself, because if younger people aren’t following what’s going on in politics, they are at a sharp disadvantage in being able to direct how politicians deal with the issues of the day" (Wattenberg 62). I question the veracity of such a statement. Is there an additional box to check on the ballot that says 'please don’t read too much into my vote I don't know what I'm talking about'? The author is making an enormous intellectual leap. He ascribes a mandated message behind one's vote that politicians are somehow supposed to suss out and convert into actionable policy. Irrespective of the individual voters reasoning - which could be well or poorly thought out - it is still one of many hundreds or thousands and cannot be counted as a directive to the politician voter in any but the loosest sense of the word.

In fact, one could take umbrage with Mr. Wattenberg’s very line of inquiry. His data set, which seeks to prove that young people are less well-informed doesn’t stand up to even basic skepticism. Claiming that in the halcyon days of the New Deal and Great Society, young people were well engaged with the hot-button stories and legislation of the day like the Taft-Hartley Act (1948) and the Civil Rights Act of 1964. However, when presented with data that shows contemporary young people were engaged in similarly important questions he cooks up this pithy dismissal: "Although the 9/ 11 Commission hearings and the abuse of Iraqi prisoners at Abu Ghraib were political stories, each had sensationalistic aspects to them that could be spun so as to provide entertainment" (Wattenberg 72).

This is selective data at its worst. The author has basically said that the fact that young people were just as tuned in to the Abu Ghraib prison scandal as older folks doesn't count because it had an entertainment value as well. Apparently the discussions of the Taft-Hartley Act in 1948 and the Civil Rights Act of 1964 were, in the author’s estimation, absolutely sober and rational debates with no sensationalistic aspects at all. Images of strikes, riots, dogs attacking protestors and police turning fire hoses on black Americans must have been totally ignored by young people in what was surely a very serious political debate with no emotions or prurient interest whatever. If one must parse the data in such a baldly arbitrary way, then there is quite likely a problem with conclusion drawn. It's easier to say young people are too busy watching Snooki cross our arms, cluck our tongues and yearn for the days of the past. Arguments about video games, entertainment and lamentations of the passing of the newspaper serve as a neat obfuscation of the type of institutional problems that disengage people from the political process at a young age. "The more than thirty year struggle of college students seeking the right to vote in college towns is a direct contradiction to the frequently accepted description of eighteen- to twenty-four-year-olds as an apathetic demographic. Quite apart from this notion of college students as politically disinterested” (Troy 612).

Another theory, less circular but perhaps equally specious is the idea that young voters are cynical and as such refuse to participate in a corrupt system.

A third theory additionally states that the youth vote suffers from the very same cost-benefit problem that suppresses voting across the board:

As a result of the relatively low turnout of young voters, it is easy to treat it as a bloc of voters that thinks about things roughly the same way. In fact, if one were successful in increasing the “youth vote” one would likely find it growing ever more disparate, wherein other demographic factors may act as better predictors.

The second misconception is that young people are equally unlikely to vote across-the-board. This is totally untrue and this fact is very informative for our discussion later on. "[I]t is a serious misconception to suppose that it is the highly educated young who are failing to turn up at the polls. On the contrary, the more education young people have, the more likely they are to vote. Education remains one of the best predictors of turnout because it provides the cognitive skills needed to cope with the complexities of politics and because it seems to foster norms of civic engagement" (Gidengil, Jamieson). Additionally, it is important to note that this is not a purely American phenomenon. Youth voting is low in every country not just the United States. "Young people in the United States are far from unique in not following public affairs and possessing relatively less knowledge of politics compared to older people. These same patterns can be found throughout the established democratic world in recent years" (Wattenberg 80).

"A misconception is that young [people] are being "turned off" by traditional electoral politics” (Gidengil). Young people are not any more turned off to the political system than anyone else. Which is to say that they are quite turned off to the system indeed.

The easiest nuts and bolts answer to why young people don’t vote is there are bureaucratic obstacles to getting registered and then getting to the polling place and voting. "The results show that 18-22 year olds are interested in the democratic process and in voting, but they lack information on absentee voting requirements and candidate issue stance. Further, results support the literature that suggests candidates do not target their campaign messages to this age group and are therefore missing an important and substantial voting audience" (Carlos, et al 1). In addition to the normal legal wrangling required to get a registration form, fill it out correctly, send it in by the deadline and do all of that without the type of experience with bureaucracy most older folks, many students go away to school and cannot vote in the district in which they reside during the school year (i.e. voting day). “Complicating matters for those students who do choose to vote by absentee ballot are the varied requirements that accompany this choice. Elections laws differ greatly from state to state with respect to procedures for applying for, and utilizing, absentee ballots. Some states allow a lengthy window in which voters may apply for an absentee ballot, while other states restrict this period to just a few weeks" (Troy 610). The fact of the matter is, the registration process is reasonably arduous and serves as an obvious barrier of entry into the voting arena. However, it is a barrier one need cross only once, so while some young people may be doggedly determined to cut through the red tape the first time out it would seem that some aren’t able to do so until they are well into their 20s, 30s or later. "[I]ndividuals in the US do not vote because the political system tends to isolate them, through both registration laws and political party arrangements. A number of other authors have pointed to registration laws as one of the main culprits for low voting turnout and the socioeconomic gap in voting" (Roksa 8).

Since there are barriers to becoming a first time voter, a young person will not always know what to expect when trying to get involved in their political process. For multiple time voters, they know where there polling place is. They know roughly how long they can expect to wait in line, what the people are going to be like, what the smells are like, etc. It may sound silly but the unknown, even for something as benign as voting can be intimidating and young people haven’t developed the voting “habit.” “Instilling voting habits in young adults would likely increase their voting turnout over the lifespan and therefore increase voting rates overall. Furthermore, existing research on young adults usually places all young adults into one category without explaining observed variation between those who do and do not vote and/or does not account for unobserved heterogeneity among young adult" (Roksa 3). In addition to not having actually experienced voting before many young voters have no experienced their first passionate political moment. Since most young people’s politics are some scrambled version of their handed-down parents politics (Lewis-Beck 140), a lot of people have not had the opportunity to develop their own partisanship or ideology. "Voting also tends to strengthen a voter's partisan attachment... The failure of young adults to turn out in large numbers may be largely due to a deficiency of such factors. As these factors develop, so will the propensity to vote, which in turn will boost those factors as well, until participation in elections is all but automatic for individuals of established age" (Lewis-Black 103). Increasing ones attachment to a certain ideology increases greatly ones likelihood to vote and while some create that attachment at an early age, for others, it takes time. Additionally, college students may face hostilities voting near their school from the local residents: "[C]ollege students often face human obstacles as well. Frequently, college students—as a whole—represent a different demographic than their surrounding neighbors. In many cases, community members feel that students are a more politically liberal group and that their interests are contrary to the community’s well-being.

A third and very difficult problem to overcome is the already calcified two-way street of ignorance that already runs between young people and politicians. "Citizens’ equality is, of course, a central component of the notion of democracy. Ordinary citizens may often mistake simple majority rule for democracy—but majority rule itself derives its powerful normative appeal from the fact that it allows each voter to have an equal influence on the outcome" (Toka 2). There is a pre-existing voter inequality problem that exists for young people. Candidates, based on past returns, cannot afford to reach out on a substantively level to the youth vote because the youth vote has been so historically underwhelming. "The present evidence suggests that the socially unequal distribution of turnout and political knowledge does introduce a systematic bias into the electoral arena. If turnout and information-level among citizens were both higher and more equal, systematically different election results may obtain—presumably forcing political parties to adjust their offering to the behavior of a different electorate" (Toka 42). There is, of course, the equally problematic counter-narrative of young people rightfully believing that their interests are not being properly represented by candidates that rarely campaign to them and are almost always at least a generation or two older. Put simply, young people have gotten the democracies they paid for with their lack of political efficacy and turning back the clock on that is going to take multiple elections:

Let’s begin with the smaller, subsidiary solutions. As we mentioned earlier, candidates have been burned over-reaching out to youth voters so one cannot blame candidates for being gun-shy to do so again. In fact, the politicians themselves are likely the least culpable party as candidates with broad appeal among youth voters like Howard Dean and Ron Paul are often running at a high-risk with little political reward. It would seem that the solution must be more holistic than a pithy “the candidates need to reach out.” However, were candidates to make a systematic attempt to reach out to young people by discussing their issue in addition to jumping on to pop culture ephemera like social media, then the youth vote would certainly turn out in greater numbers. "One very tangible form of interest is to have a campaign worker or even a candidate turn up at the door: people who reported being contacted by any of the parties during the 2000 campaign were more likely to vote" (Gidengil, et al.). However, this is not unique to or even particularly true of young voters. Any citizen who has direct contact with a candidate is far more likely to turn out to vote than one who hasn’t (Hellman). However, while the risks are well documented, there is a school of political thought that says an effective get-out-the-vote campaign directed at young people conducted by the candidates themselves could be an enormous tactical boon to the right campaign:

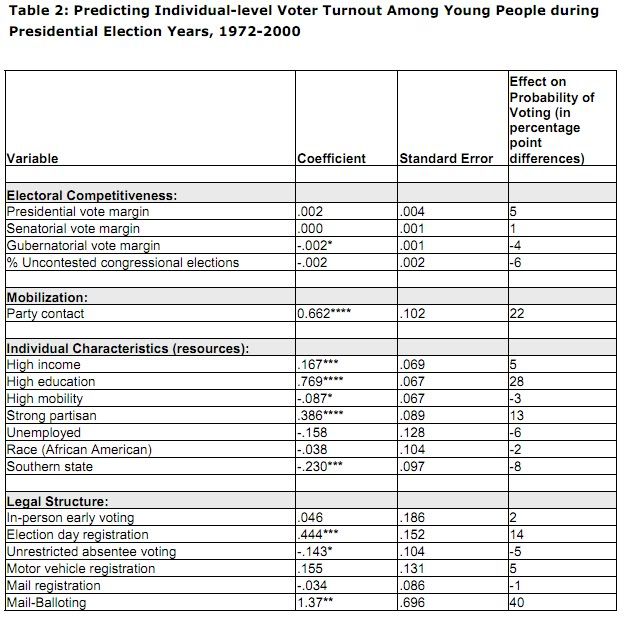

A relatively simple but powerful step would be to remove, wherever possible, any administrative boundaries that would prevent young people from exercising their franchise. "An important explanation that has been largely ignored… ever-changing obstacles—including voter intimidation, restrictive residency requirements, and unduly harsh absentee voter regulations—have at least as much, if not more, to do with keeping students from the polls" (Troy 592). College students, especially are being hit with a lot of bureaucratic red-tape. Easing or eliminating burdensome registration procedures as well as centralizing requirements would go a long way towards encouraging new voters. The problem of low voter turnout in the eighteen- to twenty-four year-old demographic is two-fold. “First, students remain largely uneducated about the requirements for voter registration and participation. Even those students that are aware of the basic legal requirements often get confused by the varying ways in which those requirements are enforced across states. Second, college students will continue to face obstacles and harassment at the polls as long as reasonable accommodations are not made to aid their participation" (Troy 612). As illustrated in the chart above less restrictive balloting including, but not limited to, mail balloting could be the single greatest boon to youth voting.

Beyond the more concrete ideas of changes in the way campaigning is done and legislating looser institutional restrictions lies the twin components to an entire universe of new voters: empowerment and education. The two can be discussed separately. Simply encouraging young people that they have the means at their disposal to make good civic decisions is meaningless without giving them the knowledge of the political system. Conversely, educating people on the manner in which our government works is a fool’s errand unless we empower them with desire to want to exercise their right. We will presuppose that part of the reason young people do not vote is that they don’t feel empowered or confident enough to do so (we will explore this idea in greater detail shortly.) Therefore "the first step in the process of empowerment involves one or more activists bringing together in a mutual-aid or self-help group or organization, people who share particular situation of disempowerment" (Breton 181). Indeed, the organization that should be in charge of this “mutual aid” must be the schools as no other institution will have the captive audience, space or manpower to convey the message to young people while they are old enough to understand but still young enough to receive it on a mass scale. Just as schools are supposed to prepare children and young adults for careers and higher education, so too should it be the schools responsibilities to turn out good citizens:

Empowering young people to feel as though they can have a hand in their own future by exercising their franchise represents a sociological and attitudinal shift. Less nebulously, what can be done from a policy perspective; are there concrete actions that can accomplish the goal of getting more young people out to vote? "[T]he single most important step would be to find ways to keep more young people in school. The more education young people have, the more interested they are in politics and the more likely they are to vote, to join groups working for change and to be active in their communities" (Gidengil, et al.). Just as was the case with the other offered solutions, critics say that education has not been enough to encourage young voters:

As we have observed, the youth themselves are often blamed for their own disengagement in politics, More people are attending school, the argument goes, so the kids themselves or parents or entertainment must be to blame for the detachment. This assumes that attending school in and of itself would provide cause people to vote – I argue however, that school is not what gives people the confidence to vote, not even education per se but the feeling of being educated; and that feeling is not being properly conveyed to students. Absolutely more youth are attending college today in real terms but sociologically it would seem that the societal emblem of "educated" is being commensurately withheld, measured not against some inert idea of what makes one "educated" or "informed" but against the totality of the rest of the population (Martin 98). As undergraduate enrollment becomes more and more the norm, increasing as it has by 67 percent between 1985 and 2007 (NCES.gov), students with an undergraduate education are being denied the confidence in their own judgment by a society and political process that states as its mantra education is the silver bullet on the one hand but shouts down the notion that even one an undergraduate education or degree one could be considered informed enough to participate in the political system.

As we have observed, the youth themselves are often blamed for their own disengagement in politics, More people are attending school, the argument goes, so the kids themselves or parents or entertainment must be to blame for the detachment. This assumes that attending school in and of itself would provide cause people to vote – I argue however, that school is not what gives people the confidence to vote, not even education per se but the feeling of being educated; and that feeling is not being properly conveyed to students. Absolutely more youth are attending college today in real terms but sociologically it would seem that the societal emblem of "educated" is being commensurately withheld, measured not against some inert idea of what makes one "educated" or "informed" but against the totality of the rest of the population (Martin 98). As undergraduate enrollment becomes more and more the norm, increasing as it has by 67 percent between 1985 and 2007 (NCES.gov), students with an undergraduate education are being denied the confidence in their own judgment by a society and political process that states as its mantra education is the silver bullet on the one hand but shouts down the notion that even one an undergraduate education or degree one could be considered informed enough to participate in the political system.

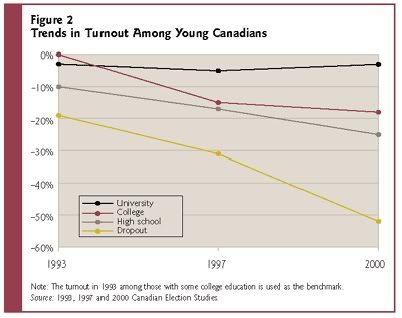

Since it seems to be axiomatically accepted and supported by the facts that the more educated a person is, young or not, then the more likely they are to vote. However, if we stratify the data a little more we see that to not exactly be true. This type of data breakdown has not been specifically studied much in American politics (though it is tangentially referenced often.) There is, however, a Canadian study available that should be similar enough to be usable as a reflection on the American political system. Whereas, in Canada, graduate student voting rates have remained nearly level, if not increased slightly, undergrads and high school graduates have dropped precipitously and surprisingly, at about the same rate. "Another study conducted by the same authors breaks up groups by lesser, middle, and better educated, and predicts likelihood of voting. Turnout for lesser educated youth at age 20 is predicted to be 29 per cent. For the middle educated it is 43 percent, and for the better educated at age 20, it is 58 per cent, which is comparable to total voter turnout for the general population" (Jerema).

It would appear that there is a confidence threshold achieved either by way of education (as represented by the graph) or by way of generalized life experience (where irrespective of education, voting rates increase in the 30s and 40s, when one usually is head of their household and possesses some authority in their professional field) when a citizen no longer feels paralyzed to act as a voter in their political system. In other words, just because people are, from an empirically observed point of view, more educated than they were decades ago doesn’t mean that they necessarily feel more educated (Martin). I must note here that this hypothesis is not necessarily one supported by academic study at this moment. It is, however, based on my admittedly limited experience, the best attitudinal explanation for the ever-diminishing returns on the youth vote. Younger voters, less sure of themselves and their opinions, fearful they might make a mistake or don’t deserve to participate due to lack of knowledge are bowing to the ever mounting societal pressure that they aren’t equipped or prepared to vote even if the law says they are (Wong 80). This type of attitudinal disconnect could be used to explain how our society, absent laws or other binding institutional ways to suppress youth, minority votes, etc. may have found a way to give some voters subtle cues that their input is not welcome: "Across a wide range of democracies, young and old, people whose income or education is low, women, racial minorities and some occupational groups tend to participate less in elections and know less about politics than other citizens" (Toka 6).

So what action does this information say we should take from a policy perspective? It says that empowerment and education must go hand-in-hand from elementary school up through high school civics if we are to agree that participation of young people is a desirable outcome.

It’s tempting to believe that current trends will continue on inexorably, but the fact of the matter is, the demographic trend of lesser involvement on the part of young people is a rather recent phenomenon. According to Wattenberg, as recently as 60 years ago, young people were more plugged in to political knowledge than senior citizens. Especially given the well established lack of knowledge or workable theories to explain it, the phenomenon could just as easily turn around in future elections. “[R]esearchers and practitioners that use [empowerment] aim to increase the capacity of individuals, organizations, and communities by focusing on assets rather than problems, and searching for environmental influences rather than blaming individuals. Establishing critical consciousness is a way to achieve this aim” (Wong 40). The rush to blame the citizens of a generation for paying too much attention to things of no consequence and not enough on items of political import is a sirens call that must be ignored because it obscures underlying societal and institutional problems that may be to blame. Surely, the citizens of my generation spent far too much mental energy remembering Homer Simpson’s home town rather than which two women have been appointed to the Supreme Court in the past 5 years. However, if one could take a time machine back to 1948, it seems a sure bet that a lot more 22 year old would be able to recognize Betty Grable than Hattie Wyatt Caraway. When people stop participating in democracy then that is an institutional failure, not a failure of the citizens. Assuming otherwise leads us down a slippery slope to elitism and nothing could be more anathema to the American Republic.

Works Cited

Bartels, Larry. "Uninformed Votes: Information Effects in Preisdential Elections." American Journal of Political Science, Vol. 40, No. 1. Feb, 1996. pp. 194-230.

Breton, Albert; Breton, Margot. "Democracy and Empowerment." Understanding democracy: economic and political perspectives. ed. Albert Breton. Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Carlos, Ray; DeMaria, Diane; Hamilton, Derrick; Huckabee, Debbie, et al. "Youth Voting Behavior" 5 April 2004.

Fitzgerald, Mary. "Easier Voting Turnout Methods Boost Youth Turnout." 2003: Circle Working Paper 1.

Gans. "Turnout Tribulations. The Journal of State Government." 65(1), 12-14, 1992.

Gidengil, Elisabeth; Blais, Andre; Nevitee, Neil; Nadeau, Richard. "Youth Participation in Politics." Electoral Insight, July 2003.

Gross, Peter. "Youth voting numbers low throughout history.", 16 December 2010.

Hellman, Emily. “Outside Contact and Young Voter Responsiveness: An Analysis of Voter Mobilization Techniques and Youth.

Jamieson et al. "U.S. Census Bureau, U.S. Dept of Commerce, Voting and Registration in the Election of November 11, 2000."

Jerema, Carson. "But university students do vote: Just because voter turnout is low for 'youth' doesn't mean it is low for all youth." 11 February 2011.

Keys, Spencer. "The youth vote is about more than just students." 29 April 2011.

Lewis-Beck, Michael. The American Voter Revisited. University of Michigan Press, 2008.

Martin, Jane Roland. "The Ideal of the Educated Person." Educational Theory. Spring 1981, Vol. 31, NO.2.

Milbrath, Lester. Political Participation. US: Rand McNally & Co. 2nd ed., April 1977.

Roksa, Josipa; Conley, Dalton. "Youth Nonvoting: Age, Class, or Institutional Constraints?" New York University Press.

Shaw, Daron. "The Effect of TV Ads and Candidate Appearances on Statewide Presidential Votes, 1988-96." The American Political Science Review, Vol. 93, No. 2. Jun., 1999. pp. 345-361.

Toka, Gabor. "Voter Inequality, Turnout and Information Effects in a Cross-National Perspective." Budapest, Hungary: Central European University Press.

Troy, Patrick, "No Place to Call Home: A Current Perspective on the Troubling Disenfranchisement of College Voter" Journal of Law & Policy, Vol 22:59, 2007.

Verba, Sidney; Nie, Norman. Participation In America: Political Democracy And Social Equality. University of Chicago Press, 1972.

Wattenberg, Martin. Is voting for young people? : with a postscript on citizen engagement. Pearson Education Inc., 2008.

Wong, Naima. "A Participatory Youth Empowerment Model and Qualitative Analysis of Student voices on Power and Violence Prevention." University of Michigan, 2008.

Researchers have advanced a number of demographic and systemic variables that could account for the low overall turnout and the decline since the 1960s. Most of this research follows Anthony Downs’ (1957) conceptualization of voting as a rational decision-making process: when benefits, either instrumental or expressive, outweigh the costs of voting (e.g., registration, learning about candidates, going to the polls), individuals are more likely to vote. This logic helps to explain the higher voting rates of more highly educated individuals (who have lower marginal costs of political information) and the negative impact of strict registration laws (which increase the time costs of voting). Yet, as the following discussion will show, this cost-benefit analysis obscures as much as it illuminates as a number of recent findings challenge the predicted patterns (Roksa 4).The solution is equally nebulous and, much to the chagrin of political scientists and economists alike, seems to defy concrete measurement. In reality, young people’s unwillingness to vote is a murky combination of institutional barriers, lack of educational resources, psychological and sociological elements. For better or worse, today’s young person needs to feel empowered to exercise their decision-making muscle, at least at first and if youth participation is considered to be a desirable outcome than many people and institutions will have to coalesce to provide that empowerment. In the past, discourse on this topic has been rife with easy, atavistic explanations that only obscure the matter. The data seems to show that pointing our collective finger at the individual citizens that make up each passing generation of youth have not achieved any desirable result. The experts quoted in this paper advocate a new model: “Empowerment efforts seek to enhance wellness, build upon strengths, and identify sociopolitical influences on quality of . An empowerment orientation, however, differs from positive youth development by placing more emphasis on the connection between the individual, micro- and macro-social structures. Empowerment, for example, assumes that many social and health problems can be attributed to unequal access to resources” (Wong 40). Removing barriers to voting legal, institutional and societal, wherever possible is the only conceivable way to increase young voter turnout.

Myths and Easy Answers

Exploring the type of easy-answer theories they have been posited in the past and subsequently revealed to be on shaky empirical ground (or outright disproven) will be instructional as we will be able to observe what misconceptions they led to and how we can avoid them in the future. One theory that seems logical enough on its face is posited in The American Voter Revisited. Lewis-Beck states that younger voters have lesser roots; that the pedantic fineries of politics may be of little interest to young people since the policies enacted don’t effect them directly:

It takes some time for the salience of politics to increase for young adults. Perhaps they are drawn into groups and associations that have a political connection, or become integrated in a community through holding a steady job or buying a home, raising a family and getting involved in local issues. All these steps would make young adults more aware of their own political interests, the impact of political decisions on these interests and the central role of political parties in the processes of governance (Lewis-Beck 149).This theory is testable from a scientific perspective since there are some young people who are married, hold down full-time jobs, have children, mortgages, etc. Based on studies conducted of younger voters, these citizens are quite a bit less likely to vote. "[P]atterns of young adults, being married decreases the likelihood of being registered, while being in school increases it. The presence of children and hours working do not seem relevant. Thus, the hypothesis that young adults increase their political participation as they acquire adult roles is not supported" (Roksa 14).

Another hypothesis, posed by Martin Wattenberg and many others, is that for various reasons - apathy, cynicism, laziness - young people are less politically knowledgeable than they were decades ago. "Today when it comes to political news stories, one could reasonably say, 'Dont ask anyone under 30,' as chances are good that he or she won’t have heard of these stories. Young adults today can hardly challenge the establishment if they don’t have a basic grasp of what is going on in the political world" (Wattenberg 61). This line of reasoning is not only reductive, it suffers from a serious chicken-egg problem. Mr. Wattenberg fails to elucidate whether or not lack of political knowledge led to lower turn-outs or the other way around. What Mr. Wattenberg does state is that for the few that still do vote, their comparative lack of knowledge leads them to be ineffective voters: "[W]e will examine data on whether people of different age groups say they have followed major political events. This is important in and of itself, because if younger people aren’t following what’s going on in politics, they are at a sharp disadvantage in being able to direct how politicians deal with the issues of the day" (Wattenberg 62). I question the veracity of such a statement. Is there an additional box to check on the ballot that says 'please don’t read too much into my vote I don't know what I'm talking about'? The author is making an enormous intellectual leap. He ascribes a mandated message behind one's vote that politicians are somehow supposed to suss out and convert into actionable policy. Irrespective of the individual voters reasoning - which could be well or poorly thought out - it is still one of many hundreds or thousands and cannot be counted as a directive to the politician voter in any but the loosest sense of the word.

In fact, one could take umbrage with Mr. Wattenberg’s very line of inquiry. His data set, which seeks to prove that young people are less well-informed doesn’t stand up to even basic skepticism. Claiming that in the halcyon days of the New Deal and Great Society, young people were well engaged with the hot-button stories and legislation of the day like the Taft-Hartley Act (1948) and the Civil Rights Act of 1964. However, when presented with data that shows contemporary young people were engaged in similarly important questions he cooks up this pithy dismissal: "Although the 9/ 11 Commission hearings and the abuse of Iraqi prisoners at Abu Ghraib were political stories, each had sensationalistic aspects to them that could be spun so as to provide entertainment" (Wattenberg 72).

This is selective data at its worst. The author has basically said that the fact that young people were just as tuned in to the Abu Ghraib prison scandal as older folks doesn't count because it had an entertainment value as well. Apparently the discussions of the Taft-Hartley Act in 1948 and the Civil Rights Act of 1964 were, in the author’s estimation, absolutely sober and rational debates with no sensationalistic aspects at all. Images of strikes, riots, dogs attacking protestors and police turning fire hoses on black Americans must have been totally ignored by young people in what was surely a very serious political debate with no emotions or prurient interest whatever. If one must parse the data in such a baldly arbitrary way, then there is quite likely a problem with conclusion drawn. It's easier to say young people are too busy watching Snooki cross our arms, cluck our tongues and yearn for the days of the past. Arguments about video games, entertainment and lamentations of the passing of the newspaper serve as a neat obfuscation of the type of institutional problems that disengage people from the political process at a young age. "The more than thirty year struggle of college students seeking the right to vote in college towns is a direct contradiction to the frequently accepted description of eighteen- to twenty-four-year-olds as an apathetic demographic. Quite apart from this notion of college students as politically disinterested” (Troy 612).

Another theory, less circular but perhaps equally specious is the idea that young voters are cynical and as such refuse to participate in a corrupt system.

Just what has impaired the development of a sense of duty to vote on the part of this generation of young Canadians is unclear, but it may well have something to do with the fact that they were reaching adulthood at a time when disaffection with politics was growing. This disaffection had a number of sources: the rise of a neo-conservative outlook that advocated a smaller role for the state, a perception that governments were relatively powerless in the face of global economic forces, and a series of constitutional crises and failed accords. All of these factors could have combined to produce a disengaged generation that often tunes out politics altogether. But these circumstances are changing. (Gidengil)Indeed, it’s difficult to reconcile the image of the naïve idealist young person with this other image of the angry, cynical young person who, as a result, refuses to participate in the process. The fact of the matter is, disaffection and cynicism are not at all the exclusive purview of the young (Gidengil) although it has had its moments where it was a common theme of a young generation: “Political disaffection peaked in the mid-1990s and seems to be waning. Meanwhile, security concerns at home and abroad have highlighted the role of the state. One result may be a renewed sense that politics does indeed matter. “

A third theory additionally states that the youth vote suffers from the very same cost-benefit problem that suppresses voting across the board:

"[T]he notorious incentive problem commonly labeled as the paradox of voting. Democracy requires that, at least at some critical junctures, many can participate in political decisions. But if many participate, the impact of a single vote on the outcome is negligible. Hence, the specifically political benefit of voting becomes unable to motivate citizens’ participation, since the cost of voting—albeit tiny—easily exceeds it. Therefore, electoral participation, at least partially, is driven by other factors than the intensity of preferences regarding election outcomes. The most likely motives seem to be a sense of citizen duty, and various pleasures that may stem from the act of voting itself.8 Thus, whatever social mechanisms generate a sense of citizen duty or entertainment value from electoral participation, the groups that appreciate them best are bound to have an advantage over the others in the electoral arena" (Toka 6).A young person, like anyone else, is very likely to take stock of their voting possibilities, realize the infinitesimal likelihood that they can really affect the outcome of an election and decide to stay home. To wit: "One interesting finding is that only about 73% believe their vote counts. When asked to identify the most important reasons for voting for a specific candidate, agreeing with candidates 28% on issues was the most frequently identified as 'most important.' This was more important than leadership, experience, and character” (Carlos, et al. 27-28). Refutation of this theory is difficult but the reason one must place this on the “easy answer” category for the purposes of this paper is that this explanation is in no way unique to young voters. Absent a particularized hypothesis of why the costs would be higher or the benefits lower to young people in particular, there’s no way to support the idea that the rational choice incentive problem particularly effects young people. As such, it is not actionable as an explanation for why young people in particular tend not to vote.

Resultant Misconceptions

As a result of the relatively low turnout of young voters, it is easy to treat it as a bloc of voters that thinks about things roughly the same way. In fact, if one were successful in increasing the “youth vote” one would likely find it growing ever more disparate, wherein other demographic factors may act as better predictors.

"Of course, anyone can invent neat theories about how a particular set of attitudes can systematically influence political involvement and, at least occasionally, vote choice, too. Suppose that the weakness of integration in the political community is an important determinant of vote choices, and, at the same time, a major cause of young people showing below average political knowledge. Then, even if the relatively ignorant young voters were to become more knowledgeable, they may not vote the same way as the currently more involved, young people do. They will still remain different from the latter with respect to an attitudinal determinant of vote choice" (Toka 23).This truism seems logical enough, but it’s worth mentioning because if we are to establish that there is no one cause for the depression of youth voting, it will very likely follow that there isn’t one solution. In fact the reason why it is important to not view the youth vote as a single bloc with a single reasoning methodology behind it will help us to understand the solution to the problem and perhaps why any solution has eluded popular political science in the first place. Often, academic and popular articles (including this one) will refer to the “youth vote” as an easy shorthand which is fine enough as long as there is the accompanying acknowledgement that there is no one “youth vote” in real terms.

The second misconception is that young people are equally unlikely to vote across-the-board. This is totally untrue and this fact is very informative for our discussion later on. "[I]t is a serious misconception to suppose that it is the highly educated young who are failing to turn up at the polls. On the contrary, the more education young people have, the more likely they are to vote. Education remains one of the best predictors of turnout because it provides the cognitive skills needed to cope with the complexities of politics and because it seems to foster norms of civic engagement" (Gidengil, Jamieson). Additionally, it is important to note that this is not a purely American phenomenon. Youth voting is low in every country not just the United States. "Young people in the United States are far from unique in not following public affairs and possessing relatively less knowledge of politics compared to older people. These same patterns can be found throughout the established democratic world in recent years" (Wattenberg 80).

"A misconception is that young [people] are being "turned off" by traditional electoral politics” (Gidengil). Young people are not any more turned off to the political system than anyone else. Which is to say that they are quite turned off to the system indeed.

“They are certainly dissatisfied with politics and politicians. Three in five believe that the government does not care what people like them think and two in five believe that political parties hardly ever keep their election promises. However, they are no more dissatisfied than older Canadians. In fact, they are, if anything, a little less disillusioned with politics than their parents and their grandparents are. In any case, political discontent is not a particularly good predictor when it comes to staying away from the polls. Many people who are disaffected with politics choose to vent that frustration by voting against the incumbent" (Gidengil, et al.)About one-third of the American adult population can be characterized as politically apathetic or passive(Milbrath). The distinction of cynicism belongs to all voters in nearly equal measure. It is a gross misconception to apply disaffection with the system to young people more than any other group.

Since there are barriers to becoming a first time voter, a young person will not always know what to expect when trying to get involved in their political process. For multiple time voters, they know where there polling place is. They know roughly how long they can expect to wait in line, what the people are going to be like, what the smells are like, etc. It may sound silly but the unknown, even for something as benign as voting can be intimidating and young people haven’t developed the voting “habit.” “Instilling voting habits in young adults would likely increase their voting turnout over the lifespan and therefore increase voting rates overall. Furthermore, existing research on young adults usually places all young adults into one category without explaining observed variation between those who do and do not vote and/or does not account for unobserved heterogeneity among young adult" (Roksa 3). In addition to not having actually experienced voting before many young voters have no experienced their first passionate political moment. Since most young people’s politics are some scrambled version of their handed-down parents politics (Lewis-Beck 140), a lot of people have not had the opportunity to develop their own partisanship or ideology. "Voting also tends to strengthen a voter's partisan attachment... The failure of young adults to turn out in large numbers may be largely due to a deficiency of such factors. As these factors develop, so will the propensity to vote, which in turn will boost those factors as well, until participation in elections is all but automatic for individuals of established age" (Lewis-Black 103). Increasing ones attachment to a certain ideology increases greatly ones likelihood to vote and while some create that attachment at an early age, for others, it takes time. Additionally, college students may face hostilities voting near their school from the local residents: "[C]ollege students often face human obstacles as well. Frequently, college students—as a whole—represent a different demographic than their surrounding neighbors. In many cases, community members feel that students are a more politically liberal group and that their interests are contrary to the community’s well-being.

A third and very difficult problem to overcome is the already calcified two-way street of ignorance that already runs between young people and politicians. "Citizens’ equality is, of course, a central component of the notion of democracy. Ordinary citizens may often mistake simple majority rule for democracy—but majority rule itself derives its powerful normative appeal from the fact that it allows each voter to have an equal influence on the outcome" (Toka 2). There is a pre-existing voter inequality problem that exists for young people. Candidates, based on past returns, cannot afford to reach out on a substantively level to the youth vote because the youth vote has been so historically underwhelming. "The present evidence suggests that the socially unequal distribution of turnout and political knowledge does introduce a systematic bias into the electoral arena. If turnout and information-level among citizens were both higher and more equal, systematically different election results may obtain—presumably forcing political parties to adjust their offering to the behavior of a different electorate" (Toka 42). There is, of course, the equally problematic counter-narrative of young people rightfully believing that their interests are not being properly represented by candidates that rarely campaign to them and are almost always at least a generation or two older. Put simply, young people have gotten the democracies they paid for with their lack of political efficacy and turning back the clock on that is going to take multiple elections:

"Suppose that there is a party advocating permissive positions on a range of moral issues, and it appeals to young people in particular. Young people, as we just saw, vote less frequently and know less than their elders. One likely consequence is that the morally permissive party ends up with a lower percentage of the vote than it would have if turnout were 100 percent and all voters equally and fully informed. The wide-ranging political consequences of this percentage difference are the price that the potential electorate of this party—i.e., those who would vote for the party if turnout were 100 percent and all voters perfectly informed—pays for voter inequality. (Toka 10)Undoing what is now decades of nearly nonexistent conversation between candidates and young voters will take time and commitment from both. "Even people who to recognize that they have a voice and that they have the right to use it will remain disempowered if they do not know how to use it or are prevented from using their voice in such a way as to be heard and to make preferences and demands known." (Breton 180).

What Can Be Done?

It’s important to realize from the outset that there is a ceiling to getting out the youth vote in America unless something drastic were implemented like mandatory voting or a change in the voting day. As such reforms seem, to put it mildly, unlikely, we will not consider them a realistic possibility. In the surge of support and civic duty that followed the passage of the 26th amendment, 48% of 18-21 year olds turned out to vote in 1972, along with 51% of 21-24 year olds. It should be understood that the solutions contained on the following pages are mild reforms and are unlikely to eclipse those 1972 numbers if implemented. That having been said, the solution to increasing voter turnout appears to be two-pronged with some small subsidiary solutions to supplement. "A substantial body of literature examines the role of socioeconomic status in voter turnout. This research reveals that individuals of higher SES, regardless whether it is measured in terms of education, income, or occupation, are more likely to vote, with education being the strongest predictor of turnout" (Roksa 5). The name of the game is simple to understand and very difficult to execute: greater education and greater empowerment of voters.Let’s begin with the smaller, subsidiary solutions. As we mentioned earlier, candidates have been burned over-reaching out to youth voters so one cannot blame candidates for being gun-shy to do so again. In fact, the politicians themselves are likely the least culpable party as candidates with broad appeal among youth voters like Howard Dean and Ron Paul are often running at a high-risk with little political reward. It would seem that the solution must be more holistic than a pithy “the candidates need to reach out.” However, were candidates to make a systematic attempt to reach out to young people by discussing their issue in addition to jumping on to pop culture ephemera like social media, then the youth vote would certainly turn out in greater numbers. "One very tangible form of interest is to have a campaign worker or even a candidate turn up at the door: people who reported being contacted by any of the parties during the 2000 campaign were more likely to vote" (Gidengil, et al.). However, this is not unique to or even particularly true of young voters. Any citizen who has direct contact with a candidate is far more likely to turn out to vote than one who hasn’t (Hellman). However, while the risks are well documented, there is a school of political thought that says an effective get-out-the-vote campaign directed at young people conducted by the candidates themselves could be an enormous tactical boon to the right campaign:

Furthermore, changes in the legal structure of voting may affect candidate campaign strategy, election dynamics, and the nature of public policy. For instance, the findings in this report indicate that political candidates, parties, and organizations would be wise to mobilize young citizens in states where voting reforms exist, particularly in states with election day registration. Moreover, those seeking youth electoral support would likely benefit by boosting voter registration rates among young people in states with convenient voting procedures (Fitzgerald 15).“[C]ampaigns could affect the electorate in many other ways. Recent scholarship offers evidence that presidential campaigns mobilize turnout, alter issue preferences and priorities, change perceptions of candidates, and inform voters" (Shaw 346).